Lecture Series on Global Culture / What is Global Culture? Chapter 3

<iframe src=”//player.vimeo.com/video/80638374″ width=”500″ height=”281″ frameborder=”0″ webkitallowfullscreen mozallowfullscreen allowfullscreen></iframe> <p><a href=”http://vimeo.com/80638374″>Lectures On Global Culture – ZHdK – CHAPTER 3: Dubai</a> from <a href=”http://vimeo.com/user22711861″>Michael Schindhelm</a> on <a href=”https://vimeo.com”>Vimeo</a>.</p>

In the previous lecture, I began outlining Dubai, that extraordinary city of extremes, as a laboratory of cultural globalisation. Regardless of the socio-political shortcomings evident there, the Gulf emirate has emerged as an alternative to its Islamic fundamentalist neighbours.

Dubai’s most striking feature is probably the speed at which the city has evolved from a slumberous trading port on the Arabian Gulf, whose pearl fishery was no more than local, to become a global metropole. Its urban population now hastens through economic experiments, social networks, and scenarios of potential cultural identity at a seemingly self-devouring pace. Strategies are devised, only to be ousted almost immediately by new strategies. Objectives set today are history tomorrow. This frenetic speed gives rise to strong fluctuations. Political or economic decisions are sometimes based upon an insufficient knowledge of a situation. Dubai, at times, resembles a beginner sat behind the steering wheel of a Ferrari careering along the fast lane full throttle. But then every experienced driver would be a beginner under Dubai’s specific social and economic conditions.

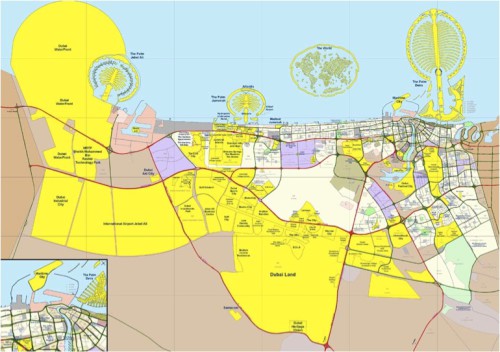

This slide shows a 2008 masterplan of the city. Presumably, Dubai’s acceleration through urban history peaked that year. At the end of 2008, the financial crisis put a temporary end to “Dubai Speed.” This map, however, reflects its planners’ unbridled determination to expand the city. The areas marked in yellow are building projects that were either still under development at the time or had not even been started. What is also apparent is how the new city has sprawled along the coastline and far into the desert. The map excerpt in the bottom-left corner shows the scale of Dubai’s urban territory before the boom since the 1970s: in those days, as you can see, the city occupied a modest area compared to today.

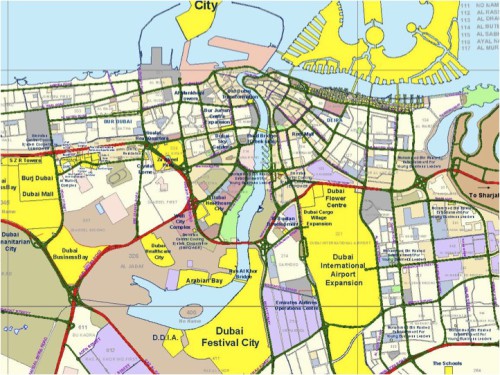

Here is large-scale reproduction of the same excerpt. In the middle of the map, we can see a natural anomaly in the coastline, a bay that cuts twenty kilometres deep into the dunes. Here, at the bay’s estuary, is where Dubai’s history began two hundred years ago. The emirati call it KHOR, which means “bay” in Arabic.

The Makhtoum, the ruling Bedouin family at the time, erected a modest fortress on the site. The sheikh recruited Iranian settlers to take up residence in the Khor estuary, to build homes there, and to establish a port. Thus, already the laying of Dubai’s foundation stone rested upon the arrival of energetic, go-getting immigrants.

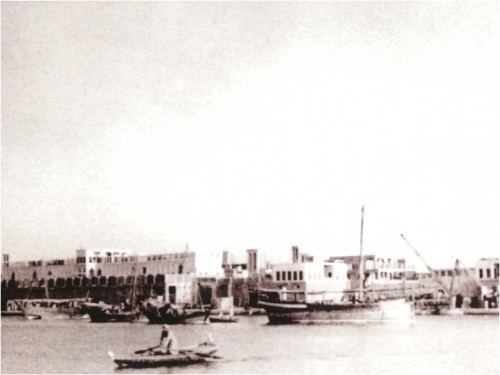

As such, it is hardly surprising that the city’s original architecture is Persian. These views of Dubai could also be of the other, the Iranian side of the Gulf. It is difficult, then, to speak of authentic architecture in the case of Dubai, because the earliest building designs, in particular of the wind towers built for climate reasons, were imported from the much further-developed neighbouring state.

The discovery of oil reserves initiated high-speed development in Dubai. The following sequence of photographs illustrates this process.

This picture shows Sheikh Zayed Road, the modern-day Champs Elysée of the Middle East, during its austere beginnings in the 1970s.

Twenty years later, the road looked like this, and another five years later, in 2010, like this.

This skyline, which boasts the world’s tallest building, the Burj Chalifa, seen here in the foreground, symbolises Dubai’s ultimate claim to be one of the world’s twenty-first-century metropolises.

But what does this history look like for the people living and working amid the furor of globalisation? In particular for those who were born and raised here, and who will most probably spend the rest of their lives in Dubai? Many older and middle-aged emirati grew up under quite different circumstances than those commonly associated with modern-day Dubai: they often attended primary school barefoot and had no running water at home. However, many of these people are today confronted with such living conditions. The past generations of traders and fishermen conducted their business at Khor Dubai, as this photograph shows, whereas today the area is a gigantic global supermarket.

Furthermore, the emirati meanwhile constitute a small minority that co-exists with a majority consisting of international immigrants, business people, and tourists. These foreign nationals, no matter whether they are low-income workers or members of the super-rich, are accustomed to an international milieu, and to foreign languages and customs. They often come from major Western or Asian countries, and are equipped with a compact, neatly packaged toolbox of cultural identity. Western immigrants, as well as those from India or China, have long brought their art and culture to Dubai. Classical concerts, Iranian pop events, Pakistani hip-hop, opera and ballet performances, exhibitions, and auctions are no longer a rarity, just as little as Hindu temples and churches, or even art and book fairs. Many of these activities have been initiated by the immigrant population itself.

With the exception of horse and camel races and falconry, local emirati-Bedouin culture, however, has missed out during Dubai’s boom and internationalisation. Until recently, schools in the region offered no art education; playing music and the fine arts were scorned. Only the young generation of today has the opportunity to engage in art. Naturally, Dubai youths are greatly interested in Western culture, also due to the influence of omnipresent popular culture and the Internet. Many young people speak English more frequently and better than Arabic, and they are more familiar with London or Paris than with the cities in their region.

As I mentioned in the previous lecture, the new twenty-first-century cities, and their laboratory-like character, lay bare in a radical way the potential conflicts and contradictions between local and global culture. As is well known, cities in countries with a traditional high culture have for some time been striving to strike a balance between the global culture increasingly on offer and their domestic culture. Whereas the West is perhaps experiencing globalisation in a softer way, this development is nevertheless taking place and affecting life and customs in these countries. Thus, English has become a major means of communication also in countries like Germany or France; the interest in foreign cities is often greater than in one’s domestic culture; and Hollywood, Walt Disney, and Harry Potter have come to dominate the arts market.

Here, in Dubai, these developments blatantly come to a head. The city, then, is not an anomaly, but an extreme case. Meanwhile, the younger generation of emirati has also begun to rethink its relationship with its own culture. Modern art, they say, is important, but especially modern Islamic art. Dubai is beginning to discover that it has had talented artists for quite some time, but so far these have hardly been taken note of. The city now has a lively theatre scene, which has been temporarily overshadowed by the commotion dominating the global events calendar. Local intellectuals are gradually becoming aware of their responsibility for reshaping Dubai as a cosmopolitan city. They are intent on not placing this responsibility in the government’s hands alone. Critical media forums and community centres have emerged, as well as a gallery scene where local and Islamic artists are establishing platforms for themselves for the first time.

How important it is to shape a cultural identity becomes plainly obvious in times of crisis. The global stock market crash of September 2008 marked a turning point in the history of Dubai. Exposed to the world markets and dependent upon international capital, the city was hit by a brutal economic crisis. The crisis was partly home-grown, in that the Dubai real estate market had produced a gigantic bubble in the years leading up to the crisis. After the city had successfully renounced “oil” as a drug, it now seemed to have become dependent upon real estate speculation. These pictures show Dubai’s famous “Palm Islands,” an artificial residential archipelago off the mainland coast. They also illustrate that an economic crisis can descend upon a city like a natural disaster.

In the years after 2008, during the subsequent economic downturn, many international nomads turned their backs on Dubai. Others who stayed discovered that one can also become unemployed and homeless in Dubai. The city was suddenly confronted with unfamiliar social challenges. Under their breaths, conservative emirate circles were wishing for a return to a Muslim society.

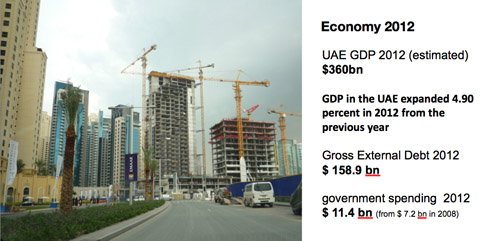

Whereas earlier economic data for Dubai signalled astronomical growth, the present forecasts are rather moderate. The city, however, seems to have overcome the crisis. Dubai is back on its feet, both economically and culturally. Or at least this is the impression that I gained on a recent visit. Downtown Dubai, with its malls, high-rise buildings, metro, and global population, has long become a narrative of the twenty-first-century city. But not everything glitters that is gold, not even in Dubai. Markets, public spaces, and reading cafés have emerged, as well as a blend of Oriental and Western public culture, which has picked up the scent of the city’s demographic reality.

The speed has eased off and life has become more normal in a certain sense, which is probably necessary for the city to find itself. In particular for the Arabic countries in the Middle East, which are yearning for social stability, Dubai has become a place of desire, a seemingly reliable alternative to fundamentalism and dictatorship. Nevertheless, the city will continue to divide opinion. It is full of contradictions and provocations. It is a frontline of globalisation. For some, it is a devastating example of global culture; for others, a fascinating one.

Translated by Mark Kyburz.