Lecture Series on Global Culture / What is Global Culture? Chapter 5

Moscow

Whoever thinks of Moscow thinks of sinister politicians like Putin or Stalin, of freezing winters, of the chiming of the Kremlin bells, of oligarchs in black limousines, or of military parades on Red Square. Whereas Moscow is not necessarily considered to be a laboratory of cultural globalisation, it is the most populated city on the European continent, ahead of Istanbul and London. It also covers the largest geographical area of all European cities. In terms of its dimensions, then, Moscow is Europe’s only real megacity.

It is not long ago that Moscow was the centre of a world system, of a global empire (see slide). From here emerged numerous social and cultural experiments, which can be subsumed under the heading of “communist tyranny.” During the first two decades of the twentieth century, the Russian avantgarde not only exerted a decisive influence on literature, painting, and music, but the movement also gave rise, for instance, to the typography and imagery used in the mass media in Russia and beyond. Moreover, Russian architects designed standard cities for the growing army of proletarian workers. And later, Soviet cosmonauts became the first human beings to enter outerspace.

For decades, the Soviet Union welcomed students from all over the world. On returning to their home countries, they became members either of the nomenclatura of socialist governments or of opposition movements in Eastern Europe, Africa, Asia, and Latin America. There are still many international students enroled in Russia’s universities today, in particular from the African region.

Despite our conventional image of Tsarism and Tolstoy’s War and Peace, the city of Mosow is a product of modernity. More than eighty percent of the city’s territory was built in the twentieth century. Its public squares and streets were planned for mass demonstrations, and the proletariat lived (and still lives) in enormous pre-fabricated concrete housing developments. The communist ideology—according to Lenin—was supposed to bring forth a new human being and thus also a new type of culture.

But that is history since the fall, in 1991, not only of the communist world empire but of the Soviet Union as well.

Russia and its capital have been a problematic sight since the end of the Soviet Union. Hordes of people, including approximately 80,000 scientists, left the country, usually for Israel, the United States, or Germany. The country’s population declined: suddenly the birth rate was half of what it was fifty years before, whereas the mortality rate was now twice as high. The number of premature deaths (as a result of alcoholism in particular) since 1991 has swelled to approximately the number of Soviet casualities in the Second World War.

Capitalism showed its ghastliest face in the country of the former class enemy, of all countries. The previous economy of scarcity was split into a mass society, which became increasingly impoverished, and an unimaginably wealthy oligarchy.

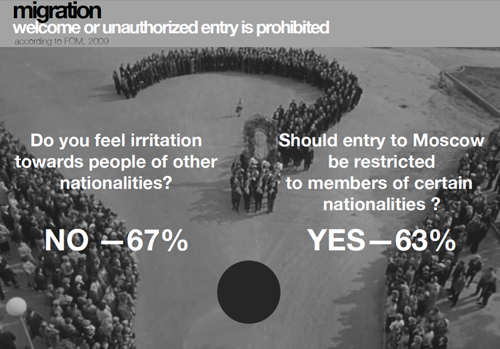

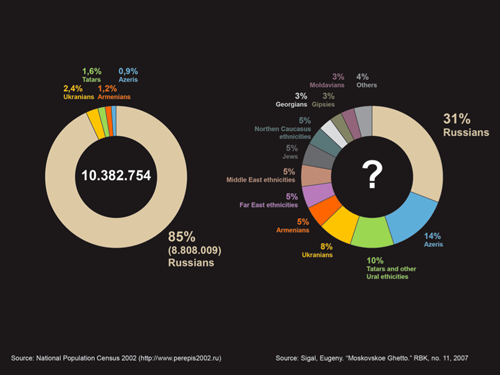

Conditions in the Russian capital convey a genuine sense of the cultural changes brought upon the country not only by the end of communism but also by globalisation. Here, in Moscow, runs the front line between reform and reaction. That frontline, moreover, is often invisible because Moscow is a huge city, a labyrinth. Due to the unreported number of illegal residents, no one knows how large the city really is. Probably, several million people live in Moscow without a residence permit. This slide suggests that data from the last population census seem to be useless. Independent analysts accuse the government of manipulating the demographic statistics in its own interests.

The proportion of foreign nationals, which is also a controversial issue, possibly amounts to one third of the city’s population. The majority is said to be Muslim. Nevertheless, relations between Moscow’s Muslim and Christian communities are permanently strained.

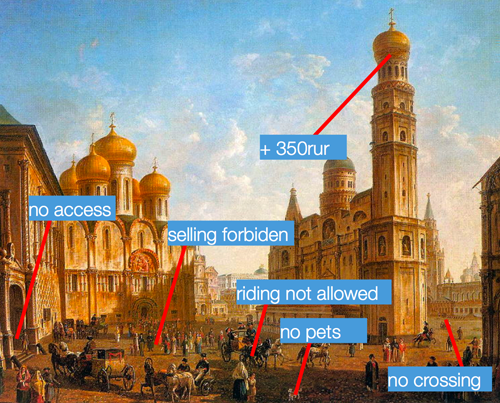

A tour of the city’s public space illustrates all these contradictions. Vladimir Putin’s government, of all governments, has turned the Kremlin, Moscow’s most prominent public space, into a source of state revenue. A few years ago, the government decided that visitors to the Kremlin castle and its grounds should be charged an entrance fee, for the first time in the city’s history.

Following a resolution by the city government, the area covered by Moscow more than doubled a few weeks ago. What appears to be a purely administrative measure may be taken to signal that the Russian government has not given up its hope of making its capital the centre of a reinvigorated superpower.

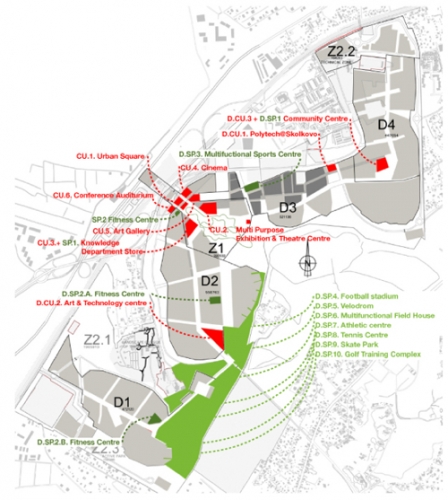

Under the slogan of overall “modernisation,” President Medvedev in 2009 announced the creation of a “Silicon Valley” just outside Moscow. He tasked an oligarch loyal to the government with implementing the plan. The Skolkovo Innovation Centre, as the development is known, is meant to redress the continuous brain drain of Russian scientists and inventors, and to attract creative minds from abroad alongside local talent. On the one hand, this project, which is gradually taking shape, embodies the tradition of the single-industry monocity common in Soviet times. The Soviet Union established several hundred such cities to drive forward the development and promotion of industry and science. The Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Akademgorodok, the Siberian City of Science, and the Baikonur Cosmodrome were well-known internationally. However, these sites were closed to foreigners.

Hence, the current project at Skolkovo also marks an attempt to guide Russian science out of its international isolation and backwardness. The reference to Silicon Valley, moreover, clearly indicates the government’s aspiration to establish an open-minded location of global science. This would indeed be an absolute novelty in Soviet and Russian history. Back in the twentieth century, the Soviet Union had done everything possible to ensure its near-total isolation. It now seems as if at least the more progressive members of the Russian leadership are seeking to establish contact with the world. Location contracts with Google, Boeing, and Siemens have already been concluded for Skolkovo. Start-ups from Russia and abroad are promised economic advantages if they decide to move to Skolkovo. Besides, the city is also meant to become a smart city, based on the latest technological and ecological considerations.

It is envisaged that 45,000 people will live in Skolkovo. In theory, the city’s population will also include Internet geeks from California, mathematicians from Bangalore, and engineers from Shenzen. However, the present-day reality of public culture in Russia is hardly prepared for this kind of globalisation. To enable Skolkovo’s international nomads, and their families, to lead a safe and comfortable life, the city would need to become a genuine laboratory of cultural globalisation, where Russian and international communication and culture would form an urban amalgam. The question will be how a laboratory for 45,000 people can emerge in the immediate proximity of a sprawling urban monster like Moscow without sealing itself off completely from its invasive neighbour. Ordinary citizens were denied access to the former Soviet monocities. Skolkovo, by contrast, is supposed to become an open city. Paradoxically, however, this experiment seems possible only if the future smart city will be protected from the nearby megacity, whose creeping xenophobia, crime, and social injustice all present major risk factors. It is difficult to imagine how an openness within such an enclosure can engender a cosmopolitan climate.

Moscow, however, is experiencing the paradoxes of cultural globalisation not only in the shape of high-level government projects. In Moscow, trouble is brewing above all at the grassroots. While Russia’s population is declining, that of its capital is growing. Moscow’s current population totals at least 12 million. Apparently, as many as 60 million Russians would prefer to live in Moscow, which amounts to no less than over forty percent of the country’s population. Thus, an urban agglomeration has come into existence in Eastern Europe that recalls the dimensions of Shanghai or Rio.

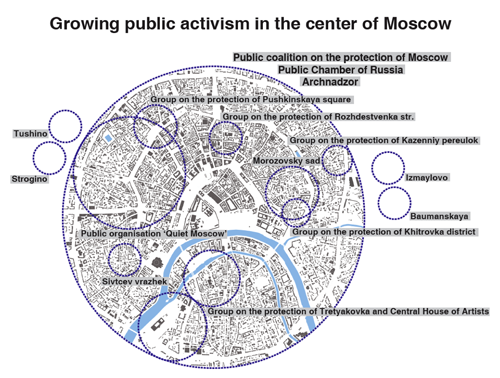

These dynamics foster new strategies for coping with everyday life. Whereas Russia’s state apparatus likes to put on show gestures of strength, day-to-day social reality often proves overwhelming, leaving the government out of its depths. Many people resort to self-help due to the failure of public administration to provide the necessary support. The former communist subbotniks, days of unremunerated volunteer work, have re-established themselves in Moscow’s micro-districts. Urban agriculture, which has become chic among today’s protest movement in the West, looks back on a long tradition in the Soviet Union’s economy of scarcity, which is now experiencing a revival.

Whereas the physical presence of foreigners has played a decisive role in initiating cultural globalisation in cities like Dubai and Hong Kong, and of course in cities in the West, in Moscow technology in particular is playing the role of the incubator. In recent years, Russia’s political and geographical isolation has turned the country into one of the world’s major consumers of electronic media.

Networks like Facebook, but above all local networks, have fundamentally changed communication patterns in Russia. Russians spend much more time using social media than the global average. Other than in China, the Internet has thus far not been subject to direct political censorship in Russia. The fierce anti-Putin movements of 2012 were often organised through social networks. Virtual public space in Russia has grown into a million-strong forum, where many discussions are held that would not be possible in real public space and that have a tremendous influence on the country’s social climate.

The impetus for debate comes from the generation of thirty to forty year olds. They form the core of the burgeoning non-parliamentary opposition. Many of these people have visited other countries, and have perhaps even studied or worked abroad. They know alternative social systems from personal experience and have clear views about what Russia lacks.

Communication technology, moreover, has helped interconnect the global protest movement. The demonstrations held on the streets of Moscow have different aims to those in Taqir Square or in Zuccotti Park on Wall Street. But the respective forms of expression, that is, the cultural technology of protest, are the same. Moscow also contributes to this expressive repertoire: Pussy Riot has long come to epitomise a culture of protest under whose auspices Madonna and Elton John can communicate with Ukrainian feminists.

Attempts at political and economic internationalisation, electronic social networks, individual self-responsibility, and sheer growth have turned Moscow, a previously grim and seemingly monochrome city, into a large-scale urban laboratory, in which subversive forms of life and expression can now compete against the familiar authoritarian modes. Europe’s only megacity is in the midst of an experiment unwanted by the state but that will unquestionably decide the future of Russia.

Cultural globalisation, then, does not always spring from immediate physical exchange between cultures otherwise foreign to each other. Information technology, as the example of Moscow shows, has become a key to disseminating global culture.

Translated by Mark Kyburz.