Lecture Series on Global Culture / What is Global Culture? Chapter 4

Hong Kong

The previous lecture revealed how Dubai, a young and fast-growing metropolis, whose local population has nomadic roots, is struggling for its own identity amid the furor of globalisation.

Whereas the traditional cultural history of the Bedouins on the Arabian Gulf has hardly advanced further than its tribal borders, Chinese and Cantonese culture in particular are is without question the world champion of expansion.

The city of Hong Kong is one of the earliest Asian metropolises. It epitomises the world of junks and opium dens, the tropical concrete jungle, and the global financial markets all at once. Like Dubai, Hong Kong is a port city. It has been considered the gate to the Middle Kingdom for at least one hundred and fifty years. Unlike Dubai, however, Hong Kong has a genuine colonial past. Local society reflects the strong British influences, for instance, on Hong Kong’s public administration and judiciary, education system, and the former colony’s economic orientation.

In 1997, when Hong Kong’s reunion with its motherland, which had turned communist forty years before, loomed, the city’s star seemed to be fading. For fear of the communists, half a million people, most of them middle class, left the city for Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Great Britain, and the United States. Similarly, the colonial elites beat a retreat, leaving the city to the economic elites of the new, ascending China. Fifteen years later, Hong Kong’s population is what it used to be: today, seven million people live in the city, and the overwhelming majority have Chinese roots.

Few cities, however, mirror the diversity of Chinese culture quite as strongly as Hong Kong. Alongside a Cantonese majority, which looks back on an autonomous political and cultural past, the city’s population includes Mainland Chinese just as much Taiwanese, Malays, or people from Singapore. Since the nineteenth century, many Chinese have commuted within the Pacific region, turning the ocean itself into a cultural space in which South-Asian, American, Canadian, and Australian influences blend with Chinese ones.

So although Hong Kong is a Chinese city, it has developed its own cosmopolitanism. Hundreds of thousands of the city’s citizens are Chinese with an international background.

Thus, at first sight, Hong Kong seems to be a “traditional” Asian city, with a vast majority of people from one and the same culture, where Asian and Western influences have thoroughly coalesced. That aside, it is not necessarily foreigners, but the Hong Kong Chinese themselves who represent the world in their city.

And yet Hong Kong is a hub not only between East and West: this slide shows one of the city’s best known buildings: the Chung King House. The filmmaker Wong Kar Wei, a star of international arthouse cinema, has portrayed the life of this building in one of his films. The Chung King House is a focal point of Afro-Indian-Chinese small trade. Here, mobile telephones for Tanzania, sunglasses for Kerala, or medicines for Mauritius are traded. Every day, traders, goods, customers, and currencies come and go …

Over time, however, matters have become more complex, especially since the reunion with mainland China. Already twenty years ago, the communist government declared the Pearl River Delta a special economic zone. The rapid economic development in this region led to a concentration of people that is second to none in the world. Megacities emerged from nowhere, right on Hong Kong’s doorstep, whose economy benefitted hugely from trade and commerce with the new zone.

Today, this economic region, which includes the new, communist city of Shenzen and Hong Kong, has a population of 19 million people alone. But if we take into account the entire Pearl River Delta, then we are talking about a population of well over 50 million. That amounts to a population approximately the size of Italy or Great Britain!

Apart from Canton (Guangzhou), the ancient imperial city situated in the western part of the region, Cantonese is not very widespread in the Pearl River Delta. Today, already 28 million mainland Chinese visit Hong Kong each year. They speak another dialect and represent another social and cultural tradition. Seen from a distance, Hong Kong and its seven million inhabitants enjoy the status of a Cantonese minority.

The presence of the mainland Chinese will further increase in the future. A few years ago, this development prompted the central government, in association with the various regional administrations, to start building a metro system that will reduce travel times between the cities in the Pearl River Delta to inner-city levels. This new rail link alone will probably bring dozens of millions of visitors to the city.

In the next few years, 40 million people are expected to board and alight from trains arriving at the high-speed line’s terminus. This is the starting point for a cultural project that helps one better appreciate how Hong Kong, as the metropolis of Cantonese and cosmopolitan culture, is trying to reshape its identity.

The future terminus station will be located in the heart of the city, on the mainland side of the Kowloon district. As these two slides show, the land separating the station from the port is currently undeveloped. This is extraordinary, given that Hong Kong is the most densely populated and virtually the most expensive city in the world. Already in 2006, the Government of Hong Kong decided to transform this area into a cultural and leisure park. A local real estate developer was commissioned to devise a master plan for the site. Both the concept and the project, however, met with fierce resistance among the local population. The projected scheme envisaged a gigantic consumer landscape beneath a large-scale roof. Hong Kong, however, had promised itself a public space, literally an open space. The city has few parks. Population density in the neighbouring city districts is as high as 140,000 people per square kilometre. The controversial development would have covered over 40 hectares (that is, 400,000 square metres).

Public protest reached a scale that ultimately forced the government to abandon the project. The proposed development plan was discarded. In its place, the government decided to develop what came to be called the West Kowloon Cultural District itself. Public funding running to $3 billion was earmarked to establish a new cultural centre at the gates of one of the world’s busiest and largest metro stations.

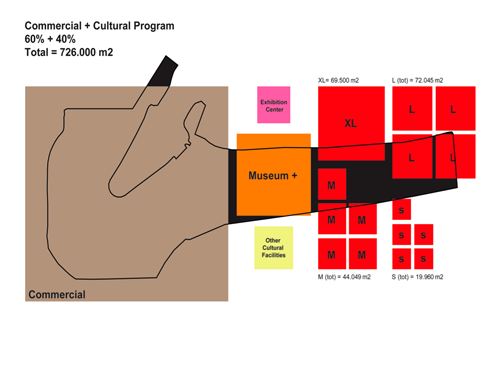

In 2008, an international competition for a master plan was launched. Seen from the perspective of conventional urban planning, the government’s plans appear monstrous. While forty percent of the area will be used as a park, the new master plan envisages a development occupying 726,000 square metres. This is approximately six times the size of Berlin’s Sony Centre. Forty percent of this area is reserved for cultural buildings, including 15 differently dimensioned theatres and concert halls, ranging from an arena resembling New York’s Madison Square Garden to various mini-stages. West Kowloon will also feature a gigantic exhibition centre and a museum of contemporary art, which is keen to be measured against legendary institutions such as the Centre Pompidou or the Museum of Modern Art.

This all sounds alarmingly large and ambitious, even more so as a tour of the city—as these slides show—reveals that Hong Kong already has a number of theatres and museums. Notwithstanding its existing cultural infrastructure, however, the city compares badly with international cultural metropoles. As yet, Hong Kong is not an important cultural location, a fact that is now supposed to change.

The West Kowloon Cultural District is but one succinct example of how and why this should happen. The concentration of over 50 million people, from a predominantly mainland Chinese background, calls for reflection on the city’s future identity. Hence, three arguments speak in favour of the West Kowloon District, probably the world’s largest cultural initiative.

First, if Hong Kong wants to assert its importance as a centre of Cantonese culture, then it must ensure that this culture remains alive and continues to be cultivated. This is particularly true for opera, the most important art form in Cantonese culture. While opera still enjoys a certain popularity, it has neither a stand-out performance venue nor its own training spaces. Hence, the West Kowloon Cultural District has first of all commissioned the development of a Xiqu theatre, that is, a Cantonese opera house. The Xiqu theatre is meant to symbolise Hong Kong’s place within Cantonese culture. Naturally, protecting the Cantonese dialect is a concern that reaches far beyond establishing a cultural infrastructure. However, the West Kowloon Cultural District will also contribute to this endeavour, among other things, by housing a central library dedicated to cultivating local literature.

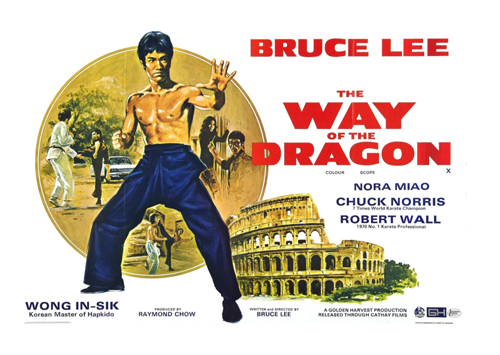

The second argument in favour of the West Kowloon Cultural District is that Hong Kong is not only part of Cantonese culture, but also a symbiosis of Western and Asian art. Whereas the Middle Kingdom often isolated itself, Hong Kong has opened its doors, with its inhabitants avidly cultivating exchange with foreign cultures. It is hardly accidental that through their decades-long success in Hollywood, Hong Kong artists like Bruce Lee or Jackie Chan have represented the image of the Asian in the global film and media world. Hong Kong’s film, games, and animation industry is a dream factory in its own right. A few years ago, when the US-American film Kungfu Panda was released and became a box office success especially in China, a Chinese media theorist summarised the matter of mutual influence as follows: “My imitation of your imitation of me, and your consumption of our consumption of you.”

Without any doubt, the West Kowloon Cultural District will heighten this particular aspect of the city’s cosmopolitan identity, that is to say, Hong Kong’s identity as a producer of global cultural content of Asian origin. A considerable portion of the cultural and commercial building programme will be devoted to the film, games, and animation industry.

And yet Hong Kong’s role as an intermediary between East and West also has a delicate side. Whereas censorship is rife in mainland China, Hong Kong enjoys freedom of speech. If Hong Kong is to safeguard its autonomy, then the freedom of art is certainly the most important mission of the West Kowloon Cultural District. While the overall concept for the district is still under development, a growing proportion of the wider public in the city is calling for the West Kowloon Cultural District to strengthen Hong Kong’s autonomy in the first instance.

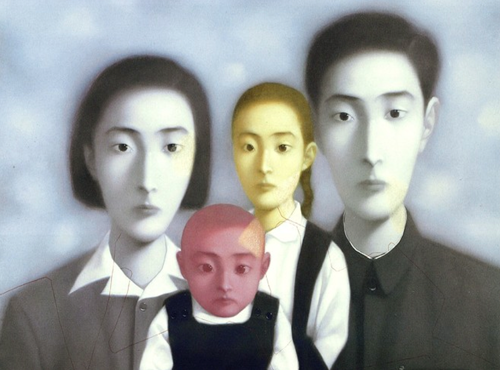

The most important project in this connection is the establishment of the M+ Museum of Contemporary Chinese Art. The museum will house the first-ever collection of contemporary domestic art on Chinese soil that is not subject to content-related or political censorship. As many prominent Chinese artists are also members of the opposition, such a museum is inconceivable in mainland China, at least for the time being.

The West Kowloon Cultural District, however, has taken the first steps toward making the M+ the frontrunner of contemporary art in Asia and China. In June 2012, the museum acquired a considerable share of the world’s largest collection of Chinese contemporary art, owned by the Swiss collector Uli Sigg. With these 1,600 works, stemming from the last forty years of Chinese art in particular, Hong Kong has thus laid the foundation for a unique collection that, at least for the moment, is impossible on the other side of the border. In the meantime, the acclaimed Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron, who already designed the Beijing Olympic Stadium, have been commissioned with building the museum. It is more than an ironic coincidence that Herzog & de Meuron are developing a museum that is meant to safeguard the freedom of Chinese contemporary art.

Finally, the third argument in favour of the West Kowloon Cultural District is that Hong Kong is the traditional trading centre in Asia. Only very few places in the world match the rich and energetic character of Hong Kong’s market culture. In this sense, the cultural market will also play a key role in Hong Kong. Art Basel, the world’s largest art fair, established an affiliate in Hong Kong in 2013. The city is already considered the most important art market of the East.

The West Kowloon Cultural District is but one example of the spirit of optimism about culture in Hong Kong. Even if some projects create the impression that they have been designed on the political drawing board, and decreed “from above,” Hong Kong’s complicated path to democracy nevertheless seems to be going through a hot phase of public participation. Thus, the decision-making process surrounding the master plan for the West Kowloon Cultural District involved over eighty public hearings.

Hong Kong, then, is also a laboratory of global culture, albeit in an entirely different sense than Dubai, which has sprung up out of the dunes of the Arabian Desert at Ferrari-like speed. Hong Kong, located on the South China Sea, aptly illustrates that “global” need not always mean “earth-spanning.” In the case of Hong Kong, “global” first and foremost means “border-crossing.” The border between the different Chinas can already comprise the whole world. Hong Kong shows that a city’s identity can consist of very different, and even supposedly opposing, elements. At one and the same time, Hong Kong is an ultramodern metropolis and yet it still has virtually untouched landscapes. Alongside Tokyo, Hong Kong is the Asian metropolis per se; quite unlike Tokyo, however, Hong Kong is full of Western influences.

Translated by Mark Kyburz.