ZHdK Lectures on Global Culture: Introduction

Introduction

In the past, I have served as the director of various theatres and operas. Time and again, my work in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, in cities such as Berlin, Dubai, Hong Kong, Beijing, and Moscow, has confronted me with the same question: What exactly is global culture?

These scenes from the “Festival of Colours,” which is part of Holi, the Indian Spring festival celebrated on the last full moon day of the month of Phalguna, convey a sense of the ecstatic atmosphere at one of the oldest festivals in the world.

This advertisement by Orange Germany, a telecommunications provider, takes up the Holi motif to woo the party generation among the company’s customers.

Perhaps these images only bear witness to the commercial exploitation of an old cultural event, but perhaps they also point to a transformation currently occurring under the influence of globalisation.

This series of a number of fifteen-minute lectures will take us on a journey, not only through various cities and countries, but also through different theories, times, and the Internet. The simplest answer to the question “What is global culture?” would be to extend the notion of culture along geographical lines, according to the following motto, as it were: in earlier times, we had a domestic culture, then a national culture, then a European culture, and now the horizon has expanded even further. However, the term “global” is not limited to what “concerns the whole world.” It is also associated with terms such as “border-crossing,” “all-embracing,” or “encompassing.” In this sense, we could posit, albeit tentatively at this stage, that global culture corresponds to the intrusion of the “big” world into the “small,” and vice versa. In one way or another, this interpenetration concerns all of us, either directly or indirectly. Its influence may be profound or negligible, come from close-by or from afar, be exerted by many or few, appear painfully or pass almost unnoticed: global culture, then, happens to all of us.

Let us begin our journey by returning to the past, to search for events that initially manifested global culture. Traditionally, globalisation on a general scale, which has grown increasingly since the second half of the twentieth century, is also considered to be the driving force behind the cultural changes that have occurred in parallel.

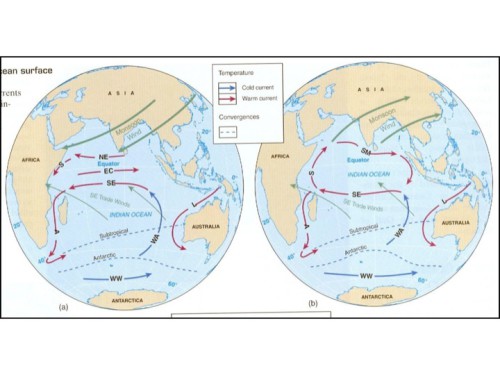

Cultural exchange, however, has existed ever since human beings invented means of transportation to cross the seas and to reach foreign shores. Already thousands of years ago, the Indian Ocean was a much-frequented waterway for human beings and cultural goods alike.

Its stable trade and monsoon winds, which blow from the north-east to the south-west in winter, and in the opposite direction in summer, ensure safe passage between Africa, India, and even Australia.

Take these shards of porcelain, for example.

They were found on a beach on Kilwa, a small island off the coast of Tanzania. The porcelain is from China. The geometrical composition of other shards suggests that they come from Iraq or Syria. Eight hundred years ago, Kilwa was a flourishing trading centre, where Indians, Arabs, and Chinese traders conducted their business.

The trading and financial empires of late-medieval Europe, such as the Monte dei Paschi or Fugger, already pursued a global strategy of sorts. The discovery and conquest of other continents since the fourteenth century also meant the discovery and conquest of other cultures. The account of Marco Polo’s travels in China, entitled Il Milione and a bestseller for centuries, stirred the possessive imagination of Columbus and his kind.

Presumably, the world did not become quite so intensely interlinked by trade and by the political, economic, and cultural appropriation of so-called colonies by their colonisers until the Europeans who travelled the world grasped the untold wealth of other cultures—China in Marco Polo’s case—and began sending back reports on what they had seen. Thus, the cultural equivalent of this worldwide networking, which we now call globalisation, already existed from the outset.

Colonialism, among other things, triggered countless cultural transformations. For instance, late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century trade expeditions and military operations abruptly transplanted African tribes that had been settled in the same territory for centuries to other regions, where these peoples were confronted with foreign languages and alien cultural habits. Not only did this colonial influence change ritual dances, but Suaheli, which was originally spoken only on the coast of East Africa, gradually became the lingua franca in the interior.

Although colonialism had profound and traumatic effects on how cultures see themselves versus how they are seen by others, the values and behavioural patterns that resulted from this experience have for some time now been superseded and influenced by political, economic, and cultural changes that we associate with globalisation in a narrow sense. These changes and influences are my subject today. Naturally, cultural globalisation did not happen overnight. Rather, it was foreshadowed by many events.

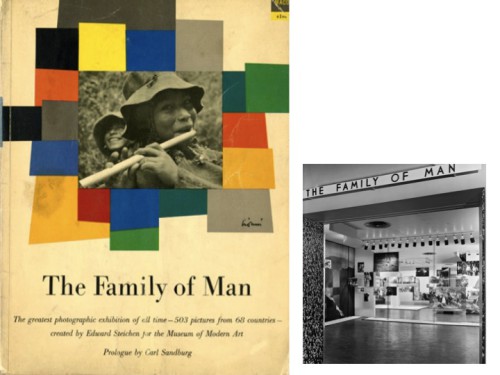

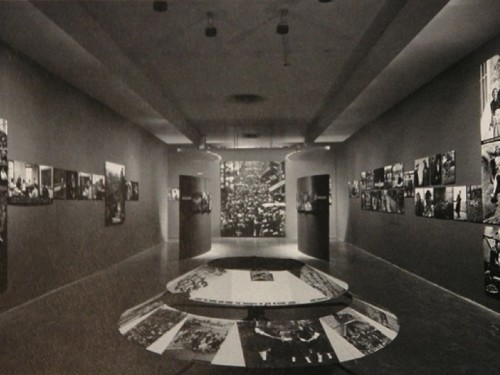

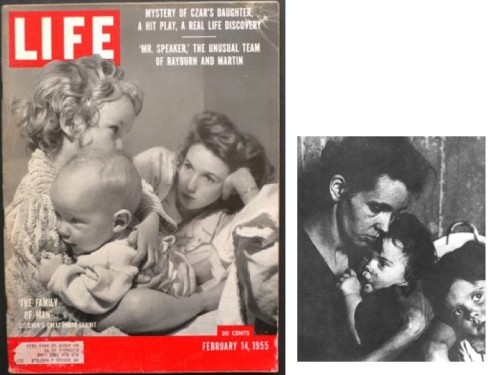

By way of example, I would like to discuss The Family of Man, a photography exhibition curated by the photographer Edward Steichen and first shown in 1955 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. After its initial display, The Family of Man subsequently toured through 38 countries across the world.

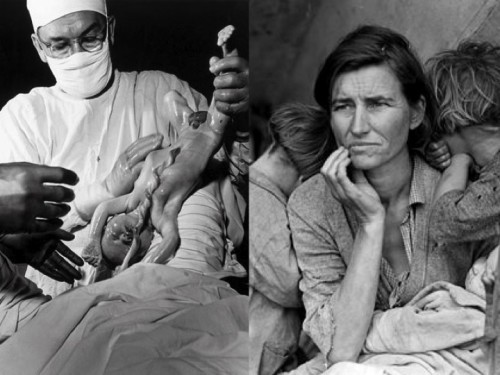

The exhibition consisted of approximately 500 photographs, taken by 273 professional and amateur photographers, which were selected from almost two million pictures. The exhibition marked an attempt to create a visual anthology of fundamental human experience, including birth, love, pleasure, illness, death, and war.

Its intention was to depict both the universal nature of such experience and the role of photography in documenting it. Soon after its opening, The Family of Man was hailed as “the greatest exhibition of all time.”

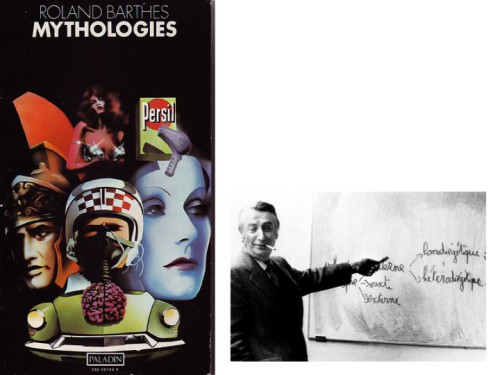

Roland Barthes, the French philosopher and semiotician, discussed Steichen’s exhibition in his book Mythologies, which was published in 1957.

Mythologies explores the mechanisms of linguistic manipulation, as observed by Barthes in the everyday culture of his time. Myth, according to Barthes, is the stealing of speech and the turning of sense into form. It is depoliticised speech. For Barthes, The Family of Man is also depoliticised speech. The myth of the human condition, he argues, rests upon the claim that we must simply dig deep enough to discover that Nature is placed at the bottom of History. The task of modern humanism, Barthes further maintains, is to uncover this age-old imposture and to “scour” the “laws” of Nature to discover History underneath.

For Barthes, The Family of Man is an example of this ancient imposture, in that the exhibition generalises, and ultimately universalises, death and birth, as well as other essential facts of the human condition. The photographs surround these scenes of elemental humanity with a poetic aura. The poetry elevates and, at the same time, conceals the social dimension of being human. Middle-class American families and the inhabitants of Brazilian favelas live and die under the same biological circumstances, but they do so under drastically different social conditions.

The basic statements of poetic photographs, claims Barthes in his discussion of Edward Steichen’s curatorial idea, lead to a justification of social inequality, since The Family of Man suggestively postulates that in front of the camera we are all equal, whether we are rich or poor, black or white. The Family of Man was shown in 38 countries during the post-war period and attracted 9 million visitors. 163 of the 273 selected photographers were Americans. Without doubt, The Family of Man was one of the first cultural goods exported on a large scale by the United States, the new superpower, to the non-Communist, post-war world. The exhibition is hence still considered a symbol of the politics of attention engaged in during the Cold War.

Barthes, the French intellectual and theorist, saw the exhibition in Paris, the former world capital of culture, which had fallen into poverty after the end of the Second World War and was now unsure of its identity. The Family of Man was undoubtedly also a sign of the American cultural universalism that would oust its French counterpart in the following decades. Insofar as that goes, I would argue that Barthes’s fierce criticism of the exhibition can be attributed, at least partly, to his vexed impression that the prerogative to interpret the human condition had suddenly shifted across the Atlantic.

The 1950s, which witnessed the advance of Hollywood, rock ’n’ roll, and fast food, marked the onset of a globalisation process that had originally begun in the United States. In the competition between political systems, the United States proved to be not only a stable and successful economy, but also a cultural power that spread its claim to hegemony not necessarily by state programmes like the Goethe Institute or the Alliance Française, but by commercial brands and services, which have stood, and still stand, for the longstanding success of American culture.

When, in 1989, the Cold War was decided almost all at once, nothing seemed more natural than the assumption, made by the American political scientist Francis Fukuyama in his book The End of History and The Last Man, that the world was moving toward a uniform world order, namely, an American-style capitalism.

The events of September 11, 2001 put an abrupt end to this dream. But it is not international terrorism alone that has changed America and the world. Especially the economic balance between East and West has shifted dramatically. In the West, the rise of China and India to globally influential economies is still largely accompanied by eloquent alarmism.

We now find ourselves not only in a multipolar world, but also in a phase of accelerated globalisation, which is no longer steered by a single superpower. Zbigniew Brzezinski, former advisor to President Jimmy Carter, recently explained why the bipolar constellation involving the United States and China need not necessarily lead to a global war: hegemony, he argues, has quite simply become impossible. Not everyone shares Brzezinski’s optimism.

This multipolar globalisation, with its lack of respect for borders, identities and traditions, is often seen as a threat. While we have long grown accustomed to the increasing internationalisation of economic and political processes, cultural globalisation is considered a danger not only by conservative strategists like Samuel Huntington. Taken together, debates over the so-called Leitkultur (the leading or core culture) in Germany, the headscarf controversy in France, the rise of fierce right-wing populist movements, especially in particularly innovative European societies such as Denmark, The Netherlands, or Switzerland, prove that cultural openness no longer necessarily enjoys majority support and that immigration cannot be promoted by multicultural tolerance alone.

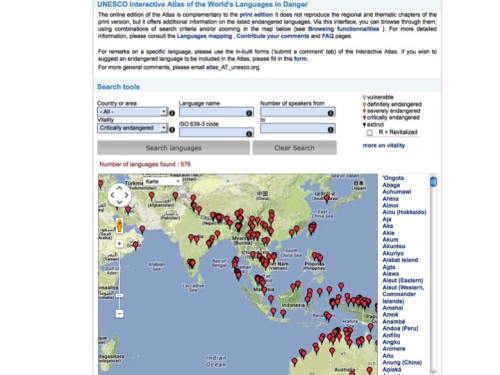

Cultural globalisation is rejected not only in the name of Leitkultur, tradition, and Christianity. It is also refuted by the political left, which regards the dissemination of Western cultural values and practices in other regions of the world as a sign of a new imperialism. McDonalds epitomises the hegemony of capitalism, which supposedly deprives the peoples of the world of the most basic need, namely, the need for indigenous eating habits. What is also observed is a convergence of cultures and a resulting loss of diversity. Last year, UNESCO actually announced that a human language dies every two weeks. Today, approximately half of the world’s six thousand languages face extinction.

These are all signs of a crisis. Familiar behavioural, decision-making, and interpretive criteria no longer work. Crises of this kind have occurred time and again in the past, for instance, with the advent of modernity or of American popular culture. Crises also call into question institutions, as well as the theory and practice of culture. As a rule, they end with the assertion of a new understanding of (cultural) phenomena, that is to say, with the rise of a new theory and practice. As history teaches us, existing theories and practices do not automatically vanish as a result of such shifts. Often, such theories and practices are expanded or complemented. The situation of artists and cultural researchers recalls that of cinema-goers watching the same film for the nth time. They know the characters, the key scenes, the outcome. This time, however, the film suddenly starts running much faster. We lose our sense of direction. We see familiar sequences, but also unfamiliar ones. We realise that the film is narrating something new. But we don’t know what. Memory doesn’t serve us. We leave the cinema—irritated or fascinated, or indeed both—and realise, moreover, that the film continues beyond the screen. It enters our everyday life, just as we become members of a cast acting out roles. Unlike in the feature film, however, no one is giving directions in this film-as-life, thus leaving us to find our roles and develop a dramaturgy.

These phenomena can also be viewed from a different perspective, namely, technological progress, modern urbanism, and sociology. And yet these phenomena remain phenomena of cultural globalisation, since they affect the Internet or urban planning just as much as the theatre or the gambling industry. This leads me to suggest that it makes sense for us to consider these phenomena together. Precisely this is the purpose of this series of lectures. The series offers us an opportunity to ask ourselves which film we are currently experiencing. Or rather, which culture are we living in?

Translated by Mark Kyburz.