ZHdK Lectures on Global Culture: North Korea and Myanmar

Moscow, the capital of Russia, which I discussed in the previous lecture, is gradually disengaging itself from its postcommunist isolation, albeit amid severe social disputes. As observed, this process is under way due to the modern forms of the international culture of protest and those of social media technology. The culture of protest and the proliferation of social networks promote the production and dissemination of global culture. By their very nature, such protests and networks are global information carriers. And yet there are still places in the world, often political exclaves, that fiercely resist globalisation. If we ask ourselves what global culture is, how it spreads, and how it emerges and is produced, then such places are also of interest. Just as an X-ray penetrates the visible body, and thereby removes it from the field of vision while detecting phenonema invisible to the naked eye, considering a non-globalising society demonstrates the tremendous role play by cultural globalisation in everyday life, precisely because such globalisation is absent in such countries.

My sixth lecture looks at two examples representative of the almost complete absence of cultural globalisation. While these cases are different, they are equally radical. Their cultural (and political) isolation is the result of dictatorship. Both countries, moreover, are located immediately adjacent to China, the country that is practising political isolation and cultural globalisation in paradoxical simultaneity.

Let us begin with a night-time view of North Korea. What we see here is a large black territory. It might sound simplistic, but this image also shows that globalisation means light. North Korea is the communist part of a country that has been divided for over sixty years, and whose southern part is one of the most progressive capitalist societies in Asia. Peace between the two Korean states is safeguarded only by a ceasefire, which is monitored by UN troops. Border disputes flare up repeatedly. North Korea is backed by the former allies Russia and China, whereas the United States and Japan stand behind South Korea.

The history of North Korea is overshadowed by a personality cult surrounding the country’s leader. This cult has been bearing strange fruit for three generations. The Beloved Leader Kim Il Sung was succeeded by the Dear Leader Kim Jong Il. Meanwhile, Kim Il Sung’s thirty-year-old grandson is causing turbulences in international foreign policy by threatening to launch a nuclear strike against South Korea and the United States.

Juche, North Korea’s state ideology, warns the country’s citizens against contact with the enemy. Thus, for instance, every foreigner is deemed a potential enemy. The Juche ideology stylises the Party and above all the Supreme Leader as a religious protector against all the evil of the world. North Koreans live in an atmosphere of constant fear and distrust. Following the total destruction wreaked by the Korean War during the 1950s, Soviet and East German engineers were tasked with rebuilding the country. Hence, the dream of a socialist modernity, which has vanished everywhere else in the world, pervades the cities of North Korea. Public life in Pyongyang recalls George Orwell’s visions in his novel 1984. Here, in the North Korean capital, the last people of a social experiment that has been abandoned everywhere else in the world walk the streets and squares, many of them dressed in uniform. And as in China under Mao, women’s hairstyles are officially sanctioned.

Looking down from the brightly coloured frescoes mounted on the brittle façades of North Korean buildings are the absurdly cheerful faces of the country’s leaders greeting their people. Pyongyang’s metro, although it was not built until the 1980s, recalls the extravagant, palace-like railway stations that Josef Stalin had built fifty years before in Moscow. This slide shows a placard of North Korea’s only daily newspaper. The state propaganda machine uses a small number of omnipresent mass media. Western sources of information do not enter into the frame here. It has to be assumed that the average North Korean hears about the world beyond the country’s borders only through local propaganda. This prevents people from gaining any sense of their bondage. Curiously, Pyongyang’s metro trains were originally used in former West Berlin. They were de-comissioned in Germany and brought to North Korea.

Even if we do not usually talk about the period of the communist world system in terms of globalisation, North Korea’s public space does seem to be a ghostly set of the soviet-style global culture that thrived during the Cold War.

In actual fact, this war is by no means over for North Korea. Party and Leader continue to gear up the “people” for a final battle, in which the enemy is becoming an increasingly abstract entity. Large-format propaganda posters abound across the country, even in rural areas. Their rhetoric recalls the Stalinist period. The “Military-First” politics, which have turned North Korea practically into a military state, begin at school. Here is a picture of a wall newspaper in a classroom of a kolkhoz school. The children are divided into tank-, airforce-, and bomber brigades.

North Korea has been almost completely isolated for twenty years. Only a few dozen Western foreigners live in the country on a permanent basis, most of them representatives of international organisations. Many countries do not even have a diplomatic mission or consular office here. Usually, only one aircraft, from Beijing, lands at Pyongyang airport a day, to return to the Chinese capital on the same day.

The collapse of the Soviet Union, North Korea’s most important ally, exacerbated the country’s isolation. Its gross domestic product is still below what it was in 1992, that is, during the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Anyone travelling around the country will come across disused industrial plants and abandoned motorways. This infrastructure suggests that at one stage North Korea was on its way to becoming a modern society. Meanwhile, however, the country—literally—has run out of energy. After sunset, its cities and kolkhozes are soon submerged in darkness. Spooky scenes, reminiscent of a medieval idyll, occur in the countryside. People are at work almost all the time, and almost exclusively with their hands. The absence of any environmental pollution submerges landscapes into the absurd magic of an untouched natural paradise. At the same time, hunger is widespread. International organisations assume that forty percent of North Korea’s population suffers from malnutrition.

And yet there are some few signs of a global influence on the country. The first Western limousines point to the emergence of an upperclass. Light and sound technology developed by Sennheiser & Co is used for the gigantic gymnastic shows held in the country’s public squares and stadiums. Concealed inside an inner-city tower block there is even something akin to a fast-food restaurant.

Presumably, China, North Korea’s mighty neighbour, is playing a decisive role in the country’s secret but uncanny transformation. The People’s Republic provides not only economic aid. Ever since international sanctions were imposed on North Korea, China has probably been using its geographical and cultural proximity to bring the country under its influence, beneath the radar of the global scrutiny. The Chinese, it seems, are able to communicate fairly effectively in North Korea, and they go largely unnoticed in everyday life. Quite possibly, a Chinese shadow economy is already emerging. The isolated instances of modern technology, affluence, and popular culture suggest that the more liberal circles among North Korea’s leadership are aspiring to a Chinese way of life.

For the time being, however, the border between North and South Korea marks the last death strip of the Cold War. Both sides desire reunification, but only on condition of their adversary’s unconditional surrender. Propaganda material, whose rhetoric echoes that of the Second World War in Europe, is frequently dropped on the opposing side’s border region. Now and again, an exchange of cross-border fire can be heard.

Immediately outside the gates of this North Korean border post, a signpost indicates that Seoul, the capital of South Korea, is seventy kilometres away. Seventy kilometres can be never-ending. Today, Seoul is one of the largest and most pulsating cities in Asia. Since Psy’s global video hit, the city’s Gangnam district has become a worldwide symbol of a new phase in pop culture. The differences between the exhausted North and the vigorous South could not be greater. Not only have their gross domestic products developed differently, but so have the physiques of their populations.Today, South Koreans are between three to eight centimetres taller than their fellow North Koreans.

It is difficult to imagine what will happen when the border between the two parts of the country opens. Isolated North Korea, however, is most certainly heading for the shock of global culture.

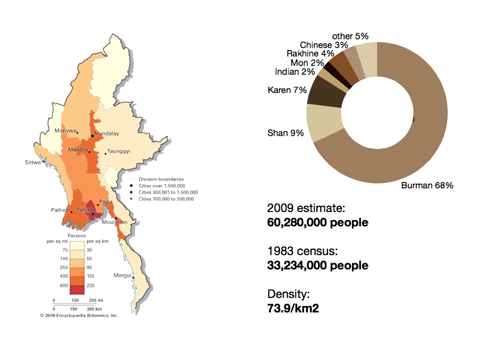

Following North Korea, my second example today takes us to Myanmar. This state lies in the opposite direction to North Korea, in the southwestern border region of the People’s Republic of China. Like North Korea, Myanmar has also been under military rule for sixty years. In recent years, however, its military rulers have made a serious effort to open up the country politically and economically. One reason for the country’s diversity is its specific geographical location: it is influenced by various climate zones, from its borders in the Himalayas to the Indian Ocean; it lies between the great cultures of India, Thailand, and China, and hence looks back on a thousand-year-old cultural history; and its population includes people from very different ethnic groups and religious denominations.

Although military rule in Myanmar has been less draconic than in North Korea, political repression and international embargoes have also left deep scars in the country’s society. Today, Myanmar is one of the poorest countries in Asia, and thus also in the world. At the same time, however, the government’s relocation from Yangoon, the old capital, which is also the country’s religious centre, to a gigantic planned city, recalls the megalomania of Ceausescu or Kim Il Sung. The country has meanwhile begun to open up. The opposition movement is headed by a prominent figure, the Nobel Peace Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. The cultural sites and the coastline in the southern part of the country are visited by tourists while international business flies into Yangoon.

The country’s diversity, however, presents a massive challenge to its modernisation. Above all the minorities living in the mountainous and scarcely populated North are causing continuous unrest. The Kachin farmers are using partisan violence to defend their opium plantations. But political autonomy is also at stake. The Kachin and Shan peoples in northern Myanmar do not speak Burmese. Their shamanism is far removed from Buddhism, which leaves these peoples isolated in their own country.

These slides show pictures taken in the state of northern Shan. People here live as primitively as they did hundreds of years ago. Meanwhile, they are receiving support from international organisations, such as Germany’s Welthungerhilfe (as seen here), with rice cultivation, water supply, or the fight against malaria. The Welthungerhilfe also runs training programmes aimed at helping the farmers organise their village economies.

Such support has become all the more important since the influx of Chinese traders from the neighbouring regions a few years ago. These traders wait for the end of the rainy season in spring, when the smallholders are using up their last rice reserves, before selling to families in need the rations needed to bridge the period until the next harvest to avoid starvation. These supplies are sold at extortionate interests rates of up to 100 percent.

The experts from the Welthungerhilfe have convinced the farmers of the benefits of setting up a community rice bank, which serves as an instrument for economic autonomy. Under this scheme, each household deposits part of its harvest in a storage overseen by the village community. Families in need receive supplies from this communal storage, which means they do not need to purchase supplies from the Chinese traders scouring the area. This slide shows the rice bank and the revenue from the sale of rice within the village community. The revenue is used to improve infrastructure, such as the construction of wells.

But the Chinese influence cannot be driven back. In Lashio, the regional capital, the market is full of Chinese goods, the bars and taverns sport Chinese advertising, and the locals watch Chinese television in their homes. Here, Burma and its military dictatorship seem very far away. At least the northern part of the country has long become both culturally and economically dependent on the mighty neighbour.

While the local farmers painstakingly tend their fields without electricity and with the help of oxcarts, Chinese engineers are using state-of-the-art technology to lay a pipeline across the country. This pipeline will convey the oil produced off the coast of Myanmar to China. The strategists of the People’s Republic are thus securing China’s natural resource reserves in the whole region.

If we imagine the nearer future of Myanmar, a country that has been isolated from international developments for sixty years, then the most likely scenario seems to be that the country will fall under an expanded Chinese sphere of influence. This is especially true for its northern territory, which is yearning for autonomy. Just as in North Korea, the Middle Kingdom is using its cultural and geographical proximity to establish a strong and stable sphere of interest in the region. In the first instance, the brightly coloured consumer world of global culture is coming to Myanmar from China. Its recent history is that of a rural country transforming into a tourism- and service-based economy, including affordable production sites, which will struggle to establish itself amid the Asian powerhouse of globalisation. The intrusion of global culture and modern technology will present a stern test for the rural communities in the North. This development will, however, provide farmers with access to the outside world and with an opportunity to actively engage with both Burmese and Chinese cultural contexts.

This lecture has discussed two examples of non-globalised societies on the threshold to the open, globally interlinked world of the twenty-first century. In both cases, it will be interesting to observe whether the next step will lead to a modern and more equitable society or not. Global culture proves to be a double-edged sword. Depending on who wields this sword, global culture can help reshape national identity or destroy the existing identity.

Translated by Mark Kyburz.