“Efficiency is for Machines, Friction for Humans” Essay for Der Tagesspiegel Berlin

An opinion piece about the future of human intelligence in the age of AI.

An American writer recently reported in the New York Times that he had moved to the country to write a novel. Lower living costs and income as a part-time copywriter initially provided a livelihood. Then AI came and took his job away. Interestingly, the writer asked his chatbot what he should do now. The chatbot recommended he buy a chainsaw. The timber trade was a far more affordable business than copywriting. So the man entered the timber trade and indeed made good income. He also overlooked the fact that his neighbors showed a slight condescension. How could a highly qualified person devote himself to such a primitive trade! Shortly after his 52nd birthday, the man got severe back pain from the hard work, and soon he had to give up his business.

Even though the story does not have a happy ending and bears witness to bitter irony (an AI is asked for advice to save oneself from the precariat caused by another AI), it is not really depressing. After all, the man knew how to help himself and made a discovery that is likely of general importance: Our judgment of what is valuable work and what is not (copywriter versus wood trader) transforms under the influence of AI.

Indeed, experts assume that the perfect world of General Artificial Intelligence promised by Silicon Valley (if it really becomes that perfect) will lead to us striving for the imperfect, for the messy, physical, and ambiguous, simply: the human. Or the chainsaw. A recurring experience since at least the industrial revolution and technical progress states: Efficiency is for machines, inefficiency for humans. One could also say: Friction. As soon as something functions smoothly, a problem is solved, humans turn to the next problem, which possibly didn’t even exist before.

Laundry washing, for example, before the electric washing machine, was brutal, all-day backbreaking work (“wash day”), which often only took place once a month or every two weeks. But with the introduction of the machine, hygiene standards rose. Since washing was now easy, it was suddenly expected that clothes be washed after a single wear. Studies (including by Ruth Schwartz Cowan) show that housewives despite the machines spent more hours per week on laundry than their grandmothers because the washing frequency increased. Technology redeemed housewives from physical exertion but created the problem-fraught need for perfect, daily cleanliness.

Since this development runs like a red thread through the history of technological progress, it can be assumed that the advance of AI will also lead to such consequences.

There are already signs of this: Generation Alpha is discovering old “dumb phones” with which one can only make calls and which have no apps. Since artworks can be created via AI, the product is no longer as important. What counts is the process. And so an audience of millions on Twitch or Tiktok watches artists for hours as they create sculptures, design video games, or formulate witty texts. At concerts, visitors must put their mobile phones into lockable neoprene pouches at the entrance. They keep the phone but cannot use it. The reports from these concerts: “No one filmed, everyone danced. We looked into each other’s eyes.” At Waldorf schools in Silicon Valley (where the children of Google and Apple managers go), screens are often taboo until high school. Graphic designers or coders who build “perfect” digital products all day sit at the potter’s wheel in the evening and produce rustic bowls.

Possibly, the takeover of many areas of life and work by AI leads to a rediscovery of purely human activities. AI as a provocation that helps us understand being human – our unique selling point – more precisely. So we will not return to a pre-digital age. AI will soon be as self-evident as the internet or even electric current. Whether a peaceful coexistence of humans and AI emerges will depend significantly on how we prepare for this transformation.

For the value of information will soon go towards zero. What counts (and costs money) is the seal of quality indicating whether the information is true or not. If the user expects primarily an “experience” from today’s technology, AI will deliver transformative experiences to him. Even without a chip in the brain, we will immerse ourselves in artificial worlds and will no longer be able to distinguish them so easily from physical reality. AI augments – expands – human consciousness. That can lead to worse problems than drug abuse.

If that is to be prevented and we want to preserve our cognitive integrity, determine our relationship to and handling of AI ourselves, schools and universities – as the most influential and independent institutions of human (natural) intelligence – must presumably rethink radically and quickly. AI could convey the impression that learning has become superfluous, for all knowledge accompanies me in my AI. And that is exactly how dependency begins.

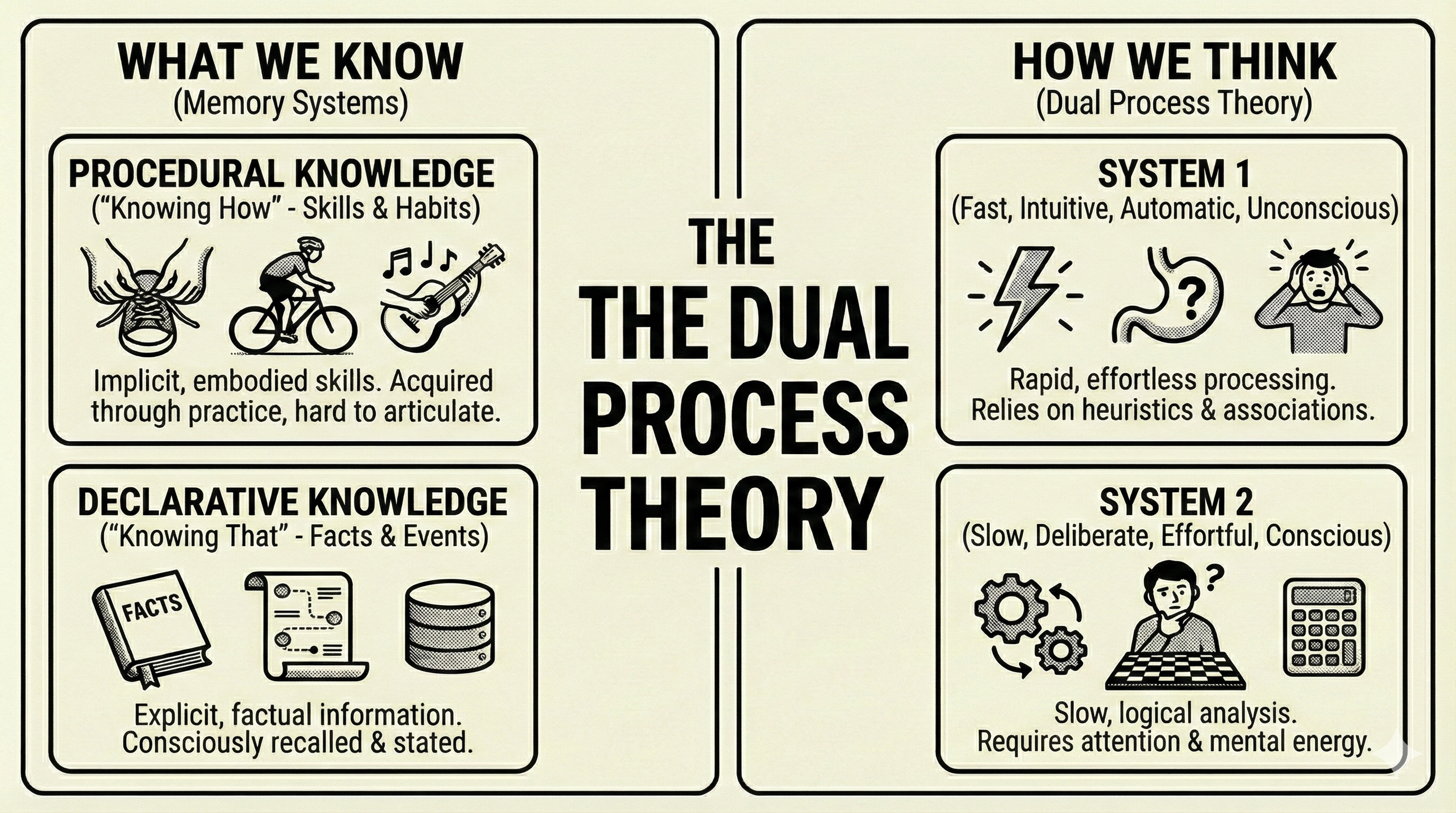

Whoever outsources thinking forgets how to do it. Teachers are already observing that students who have ideas generated by AI lose the ability to structure complex arguments in their heads. Our brain is a muscle – whoever spares it suffers muscle atrophy.

Effort would therefore have to become attractive again. When any information becomes cheap or free junk, sweat gets its price again. Schools and unis will presumably develop something like friction labs. There, exams will be oral again, and the candidate must above all know the sources of his information exactly. Professions that presuppose manual labor and empathy rise in value. New topics, fields of tasks, and branches of research will arise that presuppose genuinely human activities and competencies.

The arts will be something like the natural driving force in this process of developing a balance between humans and AI. Their disruptive competence will be needed to withstand the ubiquitous manipulation by algorithms and find the truth – the needle – in the haystack of AI-generated information streams. Artworks are testimonies of an often maximal effort that leads to an imperfect result. Moreover, artists are experts in dealing with reality and its transformation into alternative realities.

If the application and dissemination of AI is not to be left to Big Tech and their interests, a new effort is needed. Undoubtedly generally in our society, but especially where the human brain is trained. With the chainsaw one might get on the wrong track, but the question of what role we will play in our own lives in the future will not be answered by ad texts either.