Lecture Series on Global Culture / What is Global Culture? Chapter 2

This question, raised by William Shakespeare in Coriolanus (Act 3, Scene 1), is just as relevant in the twenty-first century as it was four hundred years ago.

Today’s second lecture in the series on WHAT IS GLOBAL CULTURE? looks at the role played by the city in shaping contemporary culture. Like Shakespeare, my working assumption is that the city doesn’t consist primarily of buildings, streets and squares, but of human beings, namely, its inhabitants and visitors.

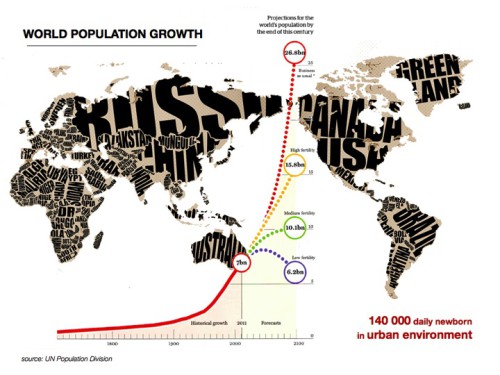

It seems as if the history of the city has been taking a dramatic turn for quite some time. The reasons for this turn are the rapid growth of the world’s population and an accompanying radical urbanisation of larger territories. Although demographic projections vary depending upon the source, almost all relevant studies suggest that the world’s population will rise up to 9 billion by the year 2100.

At the same time, experts assume that all the babies born in one day, that is, a total of 140,000 children, will live in cities in future.

Population distribution by continent is also subject to drastic change. The share of Europeans and North Americans in the world’s population will continuously decrease over the next fifty years. In 2050, Europe will make up only 7% of the global population, compared to almost three times as many Africans and eight times as many Asians.

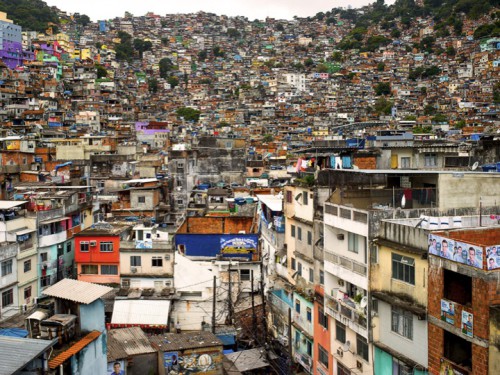

It is hardly surprising, then, that great private and public efforts are being made in the non-Western world to build cities to house the new population. A few months ago, the People’s Republic of China announced an urbanisation programme for 300 million people. Cities, however, do not come into existence on a drawing board, nor should we imagine the migration from rural areas to cities as a well-ordered, organised relocation from villages to newly built housing estates. Over the past years, large cities across the world have absorbed considerable numbers of people, in many cases, however, without being prepared for this influx of new inhabitants. Never-ending suburbs and a lack of appropriate infrastructure have emerged, creating a hodgepodge of rural and urban living conditions that eludes any familiar urbanistic classification. The term “mega-city” describes a trend toward the super-city, whose reality, however, can no longer be reconciled with the urban-planning experiences of the past.

The pace of construction work, the size of population figures, the catchment area of new inhabitants, and the complexity of the infrastructure needed for urban co-existence are all signs of our understanding of what a city is, how it comes into existence, and how it develops and rapidly changes. And yet these indicators leave us unable to make reliable predictions about even the city of the near future.

Many of these transformations are associated with large building ventures and a massive use of labour and capital. But the most dramatic change brought about by ongoing urbanisation— the assertion and reshaping of the cultural identity of a city and its inhabitants—is perhaps far less evident. Gigantic building investments are being made to obliterate historical districts in favour of new infrastructure. Cities are exchanging their role as sites of industrial production for that of service centres.

The marketing strategies adopted to attract people, capital, and creativity convey a sense of the extent to which the city has become a commodity. Does Shakespeare’s question—“What is the city but the people?”—hence enjoy the status of an advertising slogan?

The answer is certainly, albeit not exclusively, “Yes, it does.” The culture of a city, the history of its population, and the legends and anecdotes illustrating their specific character all form the substance from which concepts designed to attract tourists or capital can be formulated. At the same time, a city’s culture is a delicate and sensitive ecological system, which responds to immigration and emigration, to gentrification and tourism, and to economic downturns and upswings, often with unforeseeable consequences. Today, many of the most important economic, social, and cultural processes are taking place in cities. Change can be mild or drastic, depending on how strongly a city is exposed to these processes, which result directly from what we commonly refer to as globalisation.

Hence, the twenty-first-century city is also a laboratory for cultural globalisation. Some of the experiments conducted in this laboratory are strange, others reasonable. The activities in this laboratory are both unsettling and fascinating.

Due to their economic specifics, their particular demographics, or their climate conditions, some cities exemplify the laboratory-like character of the city of today and tomorrow. Life in these cities significantly heightens the contradictions and assumptions about the future, and lays bare processes that often remain invisible in “normal” cities.

One such city is Dubai. It embodies, without question, extreme climate, social, and economic conditions, which cannot be transferred to other cities. These extremes, however, are also the result of a particularly radical globalisation. As such they merit close attention. Tracing the development of new cities, it is worth recalling that they do not grant their citizens the same rights as Western cities do. On the other hand, we should remember that these rights were the outcome of a long social process, which still lies ahead for new cities. The history of European cities illustrates that this process often involves violence. The key question for the twenty-first century city is how to organise—and then ensure—lasting, peaceful, and equitable co-existence among its inhabitants. Since people live together differently in these new cities than, for instance, in Berlin or New York, they must also find new ways of reshaping the city as their city.

The following observations about the unusual, extreme city of Dubai rest upon two assumptions: first, Dubai is an unfinished city (and as such has its particular shortcomings and opportunities), and secondly, Dubai is a laboratory that affords us a magnified view of social and cultural events that bear witness to the transformations brought about by globalisation. These transformations, as we know, are also occurring in our part of the world in one way or another.

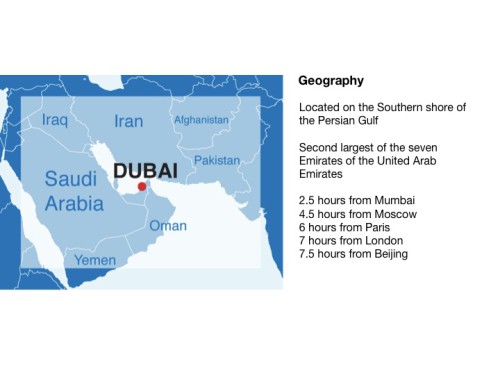

To understand the special status of Dubai, it is worth consulting a map.

Surrounded by countries like Yemen, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, or Saudi Arabia, this small Gulf emirate undoubtedly reflects a different social concept than that of its neighbouring states. Amid a region shaped by religious fanaticism and political instability, a city has emerged where people from different religious denominations and cultures are at least living together peacefully.

How did this become possible? The oil wealth of the Gulf region has been repeatedly cited as an explanation, and justifiably so. Along with six other confederates, Dubai belongs to the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The UAE ranks fifth among the oil-exporting countries belonging to OPEC, the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries. Closer scrutiny, however, reveals that Abu Dhabi, the largest of the Gulf emirates, accounts for the lion’s share of oil and gas production in the region. Dubai, by contrast, has only scant resources left.

When the region’s large oil reserves were discovered in the 1950s and 60s, it was clear that Dubai’s wealth would be shortlived. Sheikh Rashid Al Maktoum, the ruler of Dubai at the time, told his subjects that the reserves discovered on their land was a gift from Allah. In return for his gift, Allah expected the faithful to free themselves from their impoverished lives as Bedouins and to use their new wealth to establish a modern society. This is what Sheikh Rashid told his people.

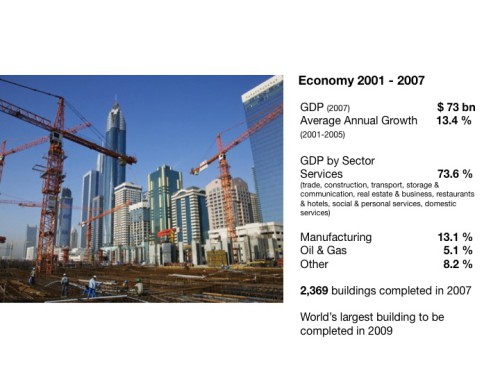

In the following decades, Dubai actually succeeded in diversifying its economy in a way unprecedented on the Arab Peninsula.

This diversification went hand in hand with remarkable growth. By the end of the last decade, one of the economically most backward regions in the Arab world had risen to become an absolute frontrunner. Currently, Dubai ranks fifth in the global tourist industry classification, boasts one of the world’s largest airports and container ports, and is a thriving global financial centre. So thanks to “Allah’s gift,” Dubai has grown into a hub situated between the West, on the one hand, and Asia and Africa, on the other. This hub is second to none in history.

But Sheikh Rashid did not rely on his emirate’s oil wealth alone for its upswing. The Bedouin chief knew very well that one can build a city only with people, that is, many talented and motivated people. In the 1960s, the Bedouins were a small people.

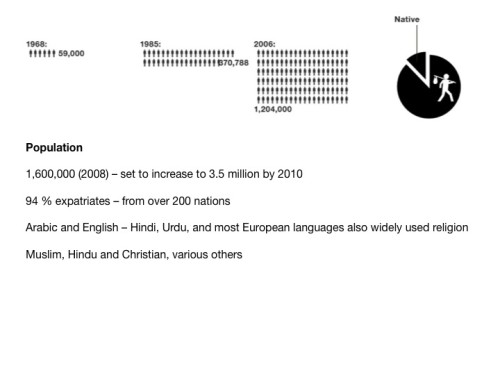

In 1968, the city’s population was 60,000. Today, approximately the same number of people live in Dubai as in Munich—1.2 million—not to mention the millions of tourists and business people who flock to the city every year.

Fast-growing cities are not an exception in the Middle or Far East. In China and India, for instance, cities ten times the size of Dubai emerged at the same time.

An essential difference between these cities, however, is that in China people have simply migrated from rural areas to the new cities. By contrast, Dubai is surrounded by nothing other than a forbidding and unpeopled desert.

Those migrating to Dubai, be they construction workers or bankers, cleaners or real-estate investors, all crossed the sand and sea by airplane. They came from all four points of the compass. They brought along their families, religion, possessions, and culture. Soon, the immigrant population outnumbered the small native population. Meanwhile, the emirati number less than ten percent of the total population of Dubai, amid a majority consisting of Indians, Chinese, Russians, Americans, Australians, and Europeans. Dubai became an incubator for a new cultural experience: here, the world was gathered in one place. Confronted with the onslaught of foreign high cultures from the West and Asia, local Bedouin culture proved to be too weak to establish a Leitkultur (a leading or core culture) of sorts. Thus, while Western Europe is pondering how to best integrate foreigners, in Dubai it was a matter of integrating the locals. I shall expand on this topic in the third lecture.

Translated by Mark Kyburz.