The Heavens over Beijing/Things of Desire

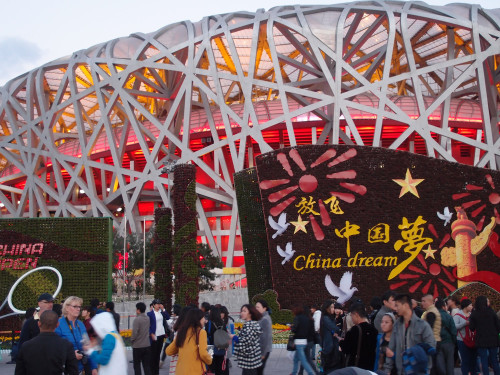

The sun hovers over the Great Hall of the People like a Chinese lantern. Two huge screens show dancers in red and blue costumes flitting from side to side in the middle of the square. Their constant smile is like the porcelain dolls on a toy clock, where the mechanism has gone seriously wrong. I think I can hear a voice. It penetrates the khaki-coloured clouds of smog above us. I recognise it, but cannot understand what it is saying. It is the President who is speaking. “This is the Chinese Dream,” he said a few months ago. Perhaps he is repeating the message to the people on the square here, where the dead chairman sleeps in his grave and where each Chinese era so far has staged its nightmares.

Things are peaceful today. But the monstrous vase with its artificial flowers as large as a parasol makes the visitors look like midgets. Policemen with broad hips and sallow faces make their way through the crowds in a state of boredom, sipping from thermos flasks. The people from the countryside are lining the square around the nation’s flagpole. The flag will soon be lowered. They eagerly watch as the guards approach to perform the ceremony. Nothing happens for several minutes. The guards and the people gaze at each other in a dreamy state for a time. The portrait of the dead chairman greets people from the other side of the street. He looks at them with insistence, but he seems to be living in a dream world too.

Then the doors of the Great Hall of the People open and young people stream out. They are students returning from the West to perform their duty for society back in their home country. They are young academics, who are not prepared to abandon their homeland at this historic time. They belong to an association celebrating China’s social success in attracting these graduates to return from the West. Fifty percent of all foreign students come back now that China offers them a better future, the country’s newspapers report. And those who remain in the West are encouraged to work for Chinese companies there. The country, after all, needs every hand and every talent. The home-comers spread out. But there is a fence in the middle of the square, dividing it into two halves. As a result, the young elite remain separated from the rest of the people on this late afternoon on Tiananmen Square.

The Chinese lantern soon appears in an anthracite-coloured mantle and quickly spreads over the city. A huge canopy emerges from an oval-shaped pond in the darkness behind the Great Hall of the People. The world of Italian opera is hidden from the Chinese city beneath it. The shadows of visitors scurry along the side of the pond. It is not easy to find the entrance. But a Chinese singer is singing the role of a Chinese princess on the stage. Chinese singers star in the roles of mandarins at the Forbidden City. These fellows appear as clowns. Puccini makes them tell the truth at the beginning of the second act: Che or sussulti e trasecoli inquieta/ come doivi lieta/ onfai die tuoi settantamila secoli/E fisce la China, addio stirpe divina. O China, o China, who now starts and leaps restlessly,/how happily you used to sleep/ filled with your/seventy thousand centuries!/ Farewell, divine lineage!/ And China comes to an end!

UNESCO is holding a conference about the future prospects of the city and the role of culture in improving living conditions. The city, say the Director-General of UNESCO and the mayor of Beijing, is the future for nearly everybody. In China too. Three hundred million people are expected to move from the villages to the city during the next two decades. A Deputy Minister of Culture is one of the people sitting on the stage. He is due to speak, according to the programme. But he remains silent and leaves the scene with the other VIPs at some stage without any explanation or message.

This is a new measure initiated by the President, Bandi (whose name has been changed) surmises; he is a colleague from Shanghai. The political elite are supposed to practise living in modesty. Even parties and celebrations have become a rare thing. Is the anti-corruption campaign part of this new asceticism? “Yes,” the colleague says. He shows me a recent report: 167,000 officials have already been checked and 148,000 punished for taking bribes. “Legal proceedings have been launched against thirty-two officials at secretary of state level,” he adds. “Politicians,” he says, “should be hard-working servants of the people. And not do a lot of talking.”

The journalists are the ones who are left to do that. A renowned professor of communications complains at a conference later that investments in culture in the country have been wasted. “Regional governments have had museums and theatres built everywhere in order to glory in the renown of iconic architecture; but these buildings now stand empty,” he says, “because the provinces do not have any collections to put on display or orchestras to present to the public. The priority should be to promote the arts and educate people in terms of culture before tackling huge property projects,” the man says, speaking into the cameras.

“Public space,” another prominent intellectual says, “is not made for people, but for cars. So China’s cities aren’t an attractive place to live in.” The man introduces a project that he got to know in Taiwan: people in one part of the city are developing green spaces, they are launching neighbourhood assistance schemes and have built a museum of local history. “Learning from Taiwan means learning about civic commitment,” the professor says. Somebody introduces a project for protecting listed buildings in Tibet. Lhasa should be restored to its former glory. So is this the Chinese Dream that the President envisions? Cultural education, citizenship, support for minorities and protecting listed buildings?

The sky only shifts the anthracite slightly today. Newspapers report that you can see for thirty metres in Harbin. Children are not allowed to do any sport outside in the capital either. The gauges are no longer able to register the degree of pollution. Airpocalpyse. The traffic on many boulevards has come to a standstill again in eight or ten lanes, as on any other day. Driving your car has nothing to do with freedom here. The government says it will introduce stricter bans on driving. That is not an attack on individual rights. (People hiding their plates to beat radars, and commonly speeding on emergency lanes, though.)

I meet an old man in a park near the Forbidden City. He is wearing a grey cap and looks at me from beneath it with kindness in his eyes. He draws characters on the granite tiles with a brush as long as a walking stick with calm movements of his arms; it all reminds me of Tai Chi. I am unable to read them, but can recognise their beauty – and the ease with which the old man creates them on the ground. However, he does not use paint, but water. As soon as he has finished a column, the previous one is dry. The old man straightens himself up, looks at the hazy sky as if he was waiting for news from there – and then continues his work.

The poisonous air mingles with incense in the Lama temple. Some of the people are tourists, but most of them come here to pray. Many of them are under thirty and may well have come here from one of the universities nearby. They hold incense sticks over their heads with their hands folded and bow down to the saintly figure. Fortune-tellers hang around at the entrance, offering people their dubious skills. The real experts do not work in public. They are in high demand at the moment. If everything in a country is changing so fast that it comes to a standstill, if the future is hidden behind a bitter haze, faith in Buddha or the skills of clairvoyants or occult practitioners increases too.

Bandi grew up in the 1970s. He can remember experiencing Mao’s death as a six-year-old. But people did not talk about it in public or in private. “It was the quietest day of his life,” he says. He wore a black ribbon on his arm when he went to school for the next six months. In his eyes, the chairman had only departed for a while. “Then in the 1980s, the people were very happy. They sang and danced on the streets, in the factories and in schools. And the chairman was always present in some kind of way. He was an enlightened and critical person,” Bandi assures me, but Mao is still a force in everyday life for him. He sometimes imagines that he is a very old man standing at the side of the third ring road at night, waving down a taxi. “What would he think about us?” Bandi says to himself in moments like these. “He doesn’t believe that he’s the exception,” he adds. “Many people have visions like these.”

People in Beijing sing much less now. But there is a man with his hands on his knees, sitting in a Chinese pavilion that is hidden in a chestnut grove, and he sings to the bare rock face opposite him in the park of the Summer Palace to the north of the city, below the Monk Tower. The man must be over 70, but his voice is still strong. He is presumably singing an old revolution song. The park is full of people, but nobody comes to this pavilion to listen to the old man. Further in the grove, a young man is practicing his first Tai Chi movements, following the instructions of a teacher. The tao, the magical power of Chinese philosophy, which flows through any trained body, does not seem to have taken hold of this man yet. He fails to cope with the first turn again and again. The old man suddenly sings “O sole mio”. The dancer gives up and disappears in the undergrowth. We are not in Naples. And the tao is only fleeting.

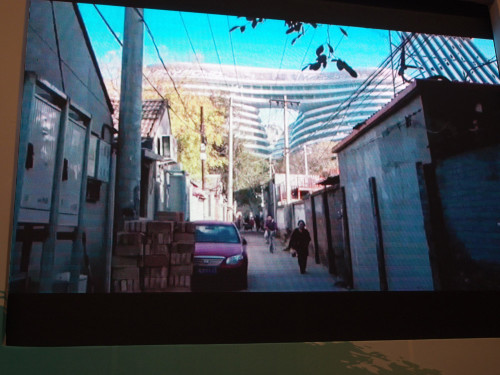

I visit a hutong restaurant with Bandi. Tripe, mules’ ears and sheep’s palate, including the jaw and teeth, are all on the menu. “The restaurant in the zoo offers fresh hippopotamus and other specialities every day,” he says. Visitors are invited to say which of the animals that people can see in the zoo tastes good. But daring journalists have now intervened. This hutong restaurant should have disappeared for the Olympic Games. But it survived. “Nevertheless, the power of the developers has become unbearable,” Bandi says. “They no longer listen to the government. Prices have risen, although the authorities have been warning of a property bubble. Liberalism just does not play a role in this country,” Bandi adds. “The President ought to do something,” he adds. “And he does seem to be acting.”

When we leave the restaurant, we pass by the inevitable glass cabinet with the photos showing the restaurant owner with prominent visitors. Bandi points to an empty space in the glass cabinet. “That’s where the photos with politicians were until just recently,” he says. As they make their way down the alley, he tells the story of the child, who was run over in a hutong a short time ago and whose body was left in the mud for an hour; none of the passers-by were bothered.

A car hits a cyclist. The man falls off and begins to moan. Other people run up and form a crowd around the injured man. A boy with an advertising bill stands in the foreground, eagerly seeking customers. The car driver gets out of his vehicle, pulls out a baseball bat and hits the cyclist on the ground a few times. Then he gets back into his car and drives off. The crowd disperses. The man is left to his own devices. He gets up and hobbles away. His t-shirt is covered with blood.

We are in Cao Fei’s film entitled “Haze and Fog”. I am sitting in her studio and she shows off her latest work, which has just had its premiere at the Frieze Art Fair in London. This is the first showing – to a small group. The scene with the cyclist reminds me of the child in the hutong. The film is a sequence of macabre and surreal miniatures where lonely people experience erotic moments in their bathtub with rubber melons, office workers dreamily squat on a children’s playground or a policeman climbs on to a balcony at night and masturbates at the sight of a half-naked young woman in bed. At some stage, a pregnant woman cuts off a finger in the kitchen and serves it to her husband in the noodle soup. The people sleepwalk through an anonymous landscape of high-rise apartment buildings. And this landscape repeatedly disappears in the haze. Then zombies come and put an end to it all. Everybody turns into zombies who gnaw on the body parts of their victims and live in an overgrown park, where old-style pavilions, which have never been completed, emerge from the jungle.

Cao Fei is in her mid-thirties and has been a leading figure in the Chinese art scene for years. She outlined the heterotopia of a Chinese city in RMB City in the online world of Second Life six years ago. The city is now used by 36 million visitors. The Internet has become the medium that the public realm cannot provide in China. Art often leads its first life in second life. The virtual and real worlds become intertwined in Cao Fei’s film “Haze and Fog”. Many of the scenes were shot in the apartment that she shares with her husband and her two children. Haze and fog are those elements that are blurring the President’s Chinese Dream temporarily.

When I leave the studio with the artist, we make our way through a hutong, which was built in the 1980s for building workers recruited from the countryside. We reach a small factory site where a fashion company has set up in business. The people there buy in tonnes of second-hand 1970s and 1980s items from the West, repair the clothes and sell them online. The company is called “olafashion”. The owner, whose husband is an artist and has exhibited works in Germany too, tells me that the name arose due to a printing error. They had actually wanted to call the company “Oldfashion”, but now believe the mistake was a twist of fate. An abandoned Buddhist temple is next door and a German artist has his studio there. The area is mainly inhabited by stray cats, but the factory still has a few workers. They are playing badminton and put their back into it as if it was a championship final. This could be a scene in a village far away in Western China. But we are only half an hour away from the Great Hall of the People, the President and the concrete jungle of the huge city and its glamour. Art has found a home on the fringes of the city. The world of art shows us China behind haze and fog.

I visit the park with the old calligrapher again. Although nobody is watching him, he continues to draw his water marks. Their message might be called the Chinese Dream.

Translated by David Strauss.